Editor's note: The following article is the second of a three-part series on the impact of advances in robotics and artificial intelligence. Today's instalment presents two conflicting scenarios concerning the impact on the job market. This week's series is excerpted from an article by Hal Ratner, the head of global research for Morningstar's investment-methodology and economic-research team. Ratner's full article is published in the August/September 2016 edition of Morningstar magazine. Part 1 is available here.

There are essentially two schools of thought on how advances in robotics and artificial intelligence will play out. We'll call one the "Creative Destruction School" in reference to the term popularized by Joseph Schumpeter's "Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy" (1942), in which continued innovation destroys one sector of the economy while creating a host of new jobs and economic opportunities in another. Such a view is popular as expressed by PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel in the Financial Times (September 2014) in a piece titled "Robots Are Our Saviours, Not the Enemy." He emphasizes that robots are extremely effective at large-scale data processing but cannot deal with ambiguity.

Invoking his former charge, PayPal, Thiel describes how computers were unable to identify fraudulent transactions due to the adaptive ingenuity of fraudsters. However, computers could identify anomalies in given transactions and send them to a human for analysis. This increased pairing of human with machine will cause displacement -- you don't need 1,000 people looking over every transaction -- but not the wholesale elimination of clerical and analytical jobs.

In a similar vein, the World Economic Forum's 2015 report, "The Future of Jobs," predicted that while there is likely to be significant dislocation over the 2015-2020 period (net job loss of 5.1 million mostly white-collar office positions), there would ultimately be the creation of new, currently unnameable jobs. However, it also points to the hollowing out of the administrative white-collar class, just as automation has led to the dislocation of blue-collar workers. By 2020, the WEF predicts that robotics, autonomous-transport artificial intelligence and machine learning will have the biggest impact on the labour force. While the report doesn't do so explicitly, it's easy to extrapolate these impact items into the future and see that they chip away at the job and wage security of the professional class.

This brings us to the second school of thought, which I'll refer to as the "Singularity School," referencing the concept made popular by mathematician and science-fiction writer Vernor Vinge (1993) of a time when computer IQ exceeds that of human beings, such that machines function on an entirely different intellectual plane -- one on which human intelligence is too limited to traverse.

Taken to its logical conclusion, this is a world where human capital becomes a near-negligible input to the production process, with machines setting wages and the few owners of machine capital entirely in control. If human capital is priced by capital investment and maintenance, we can expect rock-bottom wage rates for everyone, regardless of education and native talent.

Both the Creative Destruction School and the Singularity School have merit. The former is supported by economic history; the latter by a body of inductive reasoning that calls into question the merit of projecting the historical record forward.

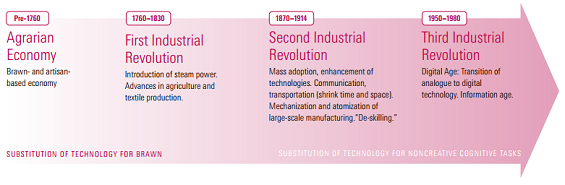

Historically in developing economies, most people worked at brawn-based activities, but others worked as artisans, blacksmiths, cabinetmakers, tailors and so forth. Although they may have employed apprentices, the skilled workers were entirely in control of the production process and typically distribution. Importantly, the factors of production were almost entirely "human factors," with physical capital constituting a minuscule proportion.

Technology led to changes in the production process itself. Improvements in steam power ushered in the first Industrial Revolution, the inception of which historians place at around 1760. The steam engine served as a direct adjunct to human brawn, which enabled the decomposition of the production process into smaller units. The improvements in productivity and, for many, quality of life were clear, but not everyone was happy. The threat of unemployment inspired weaver Ned Ludd to destroy two weaving machines and gave rise to the "Luddite" movement and a wave of anti-industrial activity across England.

The second Industrial Revolution is placed at 1870-1914, with increased mechanization of large-scale manufacturing and the refinement and mass adoption of existing technology. It also further embedded "continuous flow" (i.e., assembly line) and batch processing methods. This had the effect of both destroying many jobs but creating a host of new ones as the need for technical and administrative functions replaced those of physical labour.

Indeed, the increasing sophistication and dominance of the corporation during this period demanded such jobs. Secretaries, clerks and accountants became the lifeblood of the industrial economy. However, this period also saw the introduction of the "reproducing" machine, the machine that created other machines.

The most recent revolution is the Information Age or Digital Age. Now enormous amounts of information can be stored and transmitted quickly, if not instantaneously. The shrinkage of computers from the elephantine ENIAC computer to the mainframe and then the personal computer enormously increased their effectiveness. Moore's law (1965), which holds that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles about every two years, has held for much of recent history.

Despite the tremendous advancements made during the information age, such innovations served as complements, not just to human brawn (if indirectly) but to low-level or rote human intelligence and repetitive cognitive tasks.

Part 3: Winners and losers in the future job market (Coming soon)