As Black Friday has come and gone, bargain hunters across North America have spent hours scouring the internet to find the best deals for the holiday season. Ironically, if shoppers were to spend the same amount of time looking for good deals on investments, they probably wouldn’t worry so much about saving money on retail purchases. So what should bargain hunters look for when searching for good deals on funds?

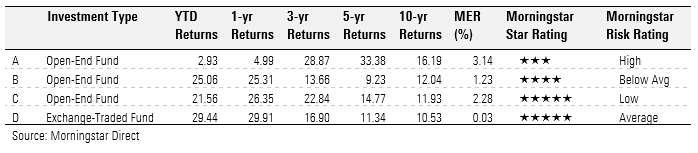

At Morningstar, we believe that fund fees are the single consistent contributing factor to a fund’s long term under or overperformance. Generally speaking, we encourage investors to look for a less expensive option wherever possible. This is evident in the way our ratings work, and consistent in the research we write. However, we also know that a cheaper fund is not always better (but often is). A good way to explain this is to have a look at the way the Morningstar Ratings for Funds (aka star rating) is calculated using four examples:

Each fund listed above are part of the same category of Canada-domiciled equity mutual funds, which means that in effect they are investing in the same universe of stocks. This is an important piece because looking at funds within the same category give us a comparable basis to work with. Which fund is the best deal?

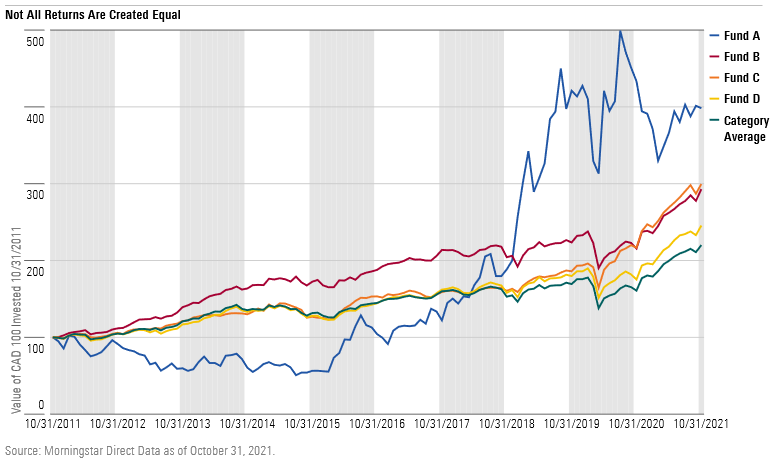

Fund A has provided the highest after-fee total returns to investors over the last decade, beating out its closest competitor by a full 400 basis points. Not an easy feat, but how did it get there?

Though it is true that Fund A provided the best after-fee returns over the last 10 years, the path it took to get there was far from a smooth ride. This roller coaster can be measured in many ways (standard deviation, Beta, max drawdown, to name a few), but Morningstar encapsulates this in a measure called the Morningstar Risk Rating, which is an integral part of our Morningstar Star Ratings. Morningstar Risk homes in on the idea that most retail investors would be indifferent between a steady fund that returns 1.65% month and a more volatile fund that is expected to return 2% a month on average (with possibilities of receiving negative 4, 2, or 8% each month). This measure of risk is used to adjust fund returns when assigning star ratings to ensure that we are not unfairly comparing funds that take on lots of risk to those that take on very little risk to arrive at similar returns. Despite the fact that the fund has had spectacular after-fee returns in the trailing 10Y period, the fact that it took on a lot of risk to get there is what detracts from its star rating (of which it receives 3 stars out of a possible 5).

Fund B and Fund C from the table alone seem similar when looking at the 10Y trailing return, and fund B charges a lower fee. So why does Morningstar give it fewer stars? In our methodology, Morningstar puts a higher weighting on more recent returns and hence fund B, though it is cheaper, is outranked by fund C, which has performed better in the near term. More recent performance puts emphasis on funds’ ability to navigate recent market conditions, and allows for funds with shorter history to be compared with those with longer history. Here, cheaper isn’t better.

Finally, we look at fund C and fund D. Fund D is offered as an ETF, and offers access at an almost negligible MER. Though it has a higher risk rating than fund C, it still places amongst the top 10% of funds within the peer group based on after-fee risk-adjusted return, it too receives 5 stars. Surprise, surprise - it’s an index fund.

What’s the Big Deal with the Star Ratings Anyway?

Nothing, really. Star ratings simply offer a look-back at funds’ performance on an even playing field after adjusting for risk and fees. The keyword here is lookback. The age-old adage of ‘past performance does not guarantee future results’ applies in full force here. However, when we look back at our ratings history, one thing did strike us – funds that have good track records as a group tend to outperform in the future. Put in other words, funds that are rated 5 stars were found more likely to remain 5-star funds than 1-star funds. In fact, in a study conducted earlier this year where we looked a how effective star ratings were in Canada over the last decade, we observed that roughly 33.1% (163/492) of 5-star funds either remained as 5-star funds or moved down to a 4-star rating, implying that they continued to outperform peers after fees. This was found to be in stark contrast to the funds that had a 1-star rating in 2010, of which only 10% (46/462) went on to outperform peers in the following 10 years. Moreover, over the last decade, 1-star funds were more than twice as likely to be liquidated or merged than a 5-star fund.

What’s the Best Deal?

All things equal, yes, the cheaper fund is a better choice. But rarely are all things equal as we’ve seen above. The star ratings help level the playing field and can provide a very good starting point for further research, and if anything, tilt the odds in the favor of the investor.

This article does not constitute financial advice. Investors are urged to conduct their own research before buying or selling securities.

.jpg)